Today I’m featuring an interesting piece of history, highlighted just this week on the Pianist Magazine’s excellent blog. The world’s first (or oldest) piano recording took place precisely 131 years ago. During this period, Arthur Sullivan (1842 – 1900) was Britain’s foremost composer, and a piano and cornet version of his song ‘The Lost Chord‘, which had been composed eleven years earlier, was the piece of music recorded to capture this moment.

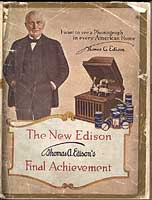

This event took place at a press conference in 1888, hosted by American Civil War recipient George Gouraud, who was introducing the phonograph, a new device for mechanical recording and reproduction of sound, which was created by American inventor Thomas Edison (1847 – 1931). Invented in 1887, the phonograph was the first device of its kind to be able to record and reproduce sound, and it heralded the beginning of a new age for the music industry. Sullivan commented rather ominously on this subject:

This event took place at a press conference in 1888, hosted by American Civil War recipient George Gouraud, who was introducing the phonograph, a new device for mechanical recording and reproduction of sound, which was created by American inventor Thomas Edison (1847 – 1931). Invented in 1887, the phonograph was the first device of its kind to be able to record and reproduce sound, and it heralded the beginning of a new age for the music industry. Sullivan commented rather ominously on this subject:

“I can only say that I am astonished and somewhat terrified at the result of this evening’s experiments: astonished at the wonderful power you have developed, and terrified at the thought that so much hideous and bad music may be put on record forever.”

You can read Pianist’s full article and listen to the recording here, but, as might be expected, the sound quality is less than ideal!

Many musicians and composers were quick to explore the phonograph’s possibilities, including Hungarian composer and pianist Béla Bartók. Bartók (1881 – 1945) was renowned for collecting folk music, alongside his colleague and fellow countryman Zoltán Kodály (1882 – 1967).

From 1904, Bartók embarked on an extensive programme of field research, travelling around Hungary and Romania, collecting a substantial selection of folk songs, frequently employing the phonograph to reliably record villagers singing and playing their folk melodies. Often considered the father of ethnomusicology, Bartók went on to write down and arrange many of those recorded tunes, and quickly became known as an expert in this field. His subsequent compositions are full of folk melodies, and this music became a fundamental influence on his work.

You can hear one of Bartók’s recordings using the phonograph by clicking on the link below:

A History of the Phonograph: Image link

The Béla Bartók Memorial House and Museum

My publications:

For much more information about how to practice piano repertoire, take a look at my piano course, Play it again: PIANO (published by Schott Music). Covering a huge array of styles and genres, the course features a large collection of progressive, graded piano repertoire from approximately Grade 1 to advanced diploma level, with copious practice tips for every piece. A convenient and beneficial course for students of any age, with or without a teacher, and it can also be used alongside piano examination syllabuses too.

You can find out more about my other piano publications and compositions here.

from Melanie Spanswick https://ift.tt/2GYGwc3